5 Programming Stata

This section is a gentle introduction to programming Stata. I discuss macros and loops, and show how to write your own (simple) programs. This is a large subject and all I can hope to do here is provide a few tips that hopefully will spark your interest in further study. However, the material covered will help you use Stata more effectively.

Stata 9 introduced a new and extremely powerful matrix programming language called Mata, and Stata expanded the choice of languages by integrating Python in version 16 and Java in version 17. In addition, it is possible to write Stata plugins in C. All of these languages are beyond the scope of this introductory tutorial. Your efforts here will not be wasted, however, because these options are complementary to -not a complete substitute for- classic Stata programming.

To learn more about programming Stata I recommend Kit Baum’s An Introduction to Stata Programming, now in its second edition, and William Gould’s The Mata Book. You may also find useful Chapter 18 in the User’s Guide, referring to the Programming volume and/or the online help as needed. Nick Cox’s regular columns in the Stata Journal are a wonderful resource for learning about Stata. Other resources were listed in Section 1 of this tutorial.

5.1 Macros

A macro is simply a name associated with some text. Macros can be local or global in scope.

5.1.1 Storing Text in Local Macros

Local macros have names of up to 31 characters and are known only in the current context (the console, a do file, or a program).

You define a local macro using

local name [=] text and you evaluate it using

`name'. (Note the use of an opening backtick or left quote

and a closing straight quote.)

The first variant, without an equal sign, is used to store arbitrary text of up to ~64k characters (up to a million in Stata SE). The text is often enclosed in quotes, but it doesn’t have to be.

Example: Control Variables in Regression.

You need to run a bunch of regression equations that include a

standard set of control variables, say age,

agesq, education, and income. You

could, of course, type these names in each equation, or you could cut

and paste the names, but these alternatives are tedious and error prone.

The smart way is to define a macro

local controls age agesq education incomeYou then type commands such as

regress outcome treatment `controls'which in this case is exactly equivalent to typing

regress outcome treatment age agesq education income.

If there’s only one regression to run you haven’t saved anything, but if you have to run several models with different outcomes or treatments, the macro saves work and ensures consistency.

This approach also has the advantage that if later on you realize

that you should have used log-income rather than income as a control,

all you need to do is change the macro definition at the top of your do

file, say to read logincome instead of income

and all subsequent models will be run with income properly logged

(assuming these variables exist).

Warning: Evaluating a macro that doesn’t exist is not an

error; it just returns an empty string. So be careful to spell macro

names correctly. If you type

regress outcome treatment `contrls', Stata will read

regress outcome treatment, because the macro

contrls does not exist. The same would happen if you type

`control' because macro names cannot be abbreviated the way

variable names can. Either way, the regression will run without any

controls. But you always check your output, right?

A Technical Note on Nested Macros

Macro definitions may include other macros. For example we could

define age and then use it in controls:

local age "age agesq"

local controls `age' education incomeThe first ocurrence of age in the first line is the name

of the macro, and the second occurrence the name of a variable. I used

quotes to make the code clearer, but they are optional. Stata never gets

confused.

The macro age in the definition of controls

is resolved at the time the macro is defined, not when it is evaluated.

Therefore changing the contents of age at a later time will

not change controls. Suppose you run a few models and then

decide to control for age using age5, a factor variable

with age in five-year groups. You define local age i.age5.

The problem is that controls still has age and

agesq.

There is, however, a way to achieve that particular effect. The trick

is to escape the macro evaluation character when you define the outer

macro, typing local controls \`age' education income. Now

Stata does not evaluate the inner macro (but eats the escape character),

so the contents of controls becomes

`age' education income. When the controls

macro is evaluated, Stata sees that it includes the macro

age and substitutes its current contents.

In one case substitution occurs when the macro is defined, in the other when it is evaluated.

5.1.2 Storing Results in Local Macros

The second type of macro definition, local name = text

with an equal sign, is used to store results. It instructs

Stata to treat the text on the right hand side as an expression,

evaluate it, and store a text representation of the result under the

given name.

Suppose you just run a regression and want to store the resulting

R-squared, for comparison with a later regression. You know that

regress stores R-squared in e(r2), so you

think local rsq e(r2) would do the trick. Well, does

it?

Your macro stored the formula e(r2), as you can see by

typing display "`rsq'". What you needed to store was the

value. The solution is to type local rsq = e(r2), with an

equal sign. This causes Stata to evaluate the expression and store the

result.

To see the difference try this

. sysuse auto, clear (1978 automobile data) . quietly regress mpg weight . local rsqf e(r2) . local rsqv = e(r2) . di `rsqf' // this has the current R-squared .65153125 . di `rsqv' // as does this .65153125 . quietly regress mpg weight foreign . di `rsqf' // the formula has the new R-squared .66270291 . di `rsqv' // this guy has the old one .65153125

Another way to force evaluation is to enclose e(r2) in

single quotes when you define the macro. This is called a macro

expression, and is also useful when you want to display results. It

allows us to type display "R-squared=`rsqv'" instead of

display "R-squared=" `rsq'. (What do you think would happen

if you type display "``rsqf''"?)

An alternative way to store results for later use is to use

scalars (type help scalars to learn more.) This

has the advantage that Stata stores the result in binary form without

loss of precision. A macro stores a text representation that is good

only for about 8 digits. The downside is that scalars are in the global

namespace, so there is a potential for name conflicts, particular in

programs (unless you use temporary names, which we discuss later).

You can use an equal sign when you are storing text, but

this is not necessary, and is not a good idea if you are using an old

version of Stata. The difference is subtle. Suppose we had defined the

controls macro by saying

local controls = "age agesq education income". This would

have worked fine, but the quotes cause the right-hand-side to be

evaluated, in this case as a string, and strings used to be

limited to 244 characters (or 80 in Stata/IC before 9.1), whereas macro

text can be much longer. Type help limits to be reminded of

the limits in your version.

5.1.3 Keyboard Mapping with Global Macros

Global macros have names of up to 32 characters and, as the name indicates, have global scope.

You define a global macro using

global name [=] text and evaluate it using

$name. (You may need to use ${name} to clarify

where the name ends.)

I suggest you avoid global macros because of the potential for name conflicts. A useful application, however, is to map the function keys on your keyboard. If you work with a repository on GitHub, for example, try something like this

global F5 https://raw.githubusercontent.com/username/repositoryname/main

Then when you hit F5 Stata will substitute the full name. And you can

execute a do file in the repository using

do $F5/dofilename. (The use of a

/ makes it clear where the macro name ends, and we just

append the name of the do file.)

Obviously you don’t want to type this macro each time you use Stata.

Solution? Enter it in your profile.do file, a set of

commands that is executed each time you run Stata.

To learn where to store your profile type help profile

and then follow the link for your operating system, as there are some

differences between Windows, Mac and Unix computers.

5.1.4 More on Macros

Macros can also be used to obtain and store information about the system or the variables in your dataset using extended macro functions. For example you can retrieve variable and value labels, a feature that can come handy in programming.

There are also commands to manage your collection of macros,

including macro list and macro drop. Type

help macro to learn more.

5.2 Looping

Loops are used to do repetitive tasks. Stata has commands that allow looping over sequences of numbers and various types of lists, including lists of variables.

Before we start, however, don’t forget that Stata does a lot of looping all by itself. If you want to compute the log of income, you can do that in Stata with a single line:

gen logincome = log(income)This loops implicitly over all observations, computing the log of each income, in what is sometimes called a vectorized operation. You could code the loop yourself, but you shouldn’t because (i) you don’t need to, and (ii) your code will be a lot slower that Stata’s built-in loop.

5.2.1 Looping Over Sequences of Numbers

The basic looping command takes the form

forvalues number = sequence {

... body of loop using `number' ...

}Here forvalues is a keyword, number is the

name of a local macro that will be set to each number in the sequence,

and sequence is a range of values which can have the

form

min/maxto indicate a sequence of numbers frommintomaxin steps of one, for example1/3yields 1, 2 and 3, orfirst(step)lastwhich yields a sequence fromfirsttolastin steps of sizestep. For example15(5)50yields 15,20,25,30,35,40,45 and 50.

(There are two other ways of specifying the second type of sequence,

but I find the one listed here the clearest, see

help forvalues for the alternatives.)

The opening left brace must be the last thing on the first line

(other than comments), and the loop must be closed by a matching right

brace on a line all by itself. The loop is executed once for each value

in the sequence with your local macro number (or whatever

you called it) holding the value.

Creating Dummy Variables

Here’s my favorite way of creating dummy variables to represent age

groups. Stata 11 introduced factor variables and Stata 13 improved

the

labeling of tables of estimates, so there’s really no need to “roll your

own” dummies, but the code remains instructive.

forvalues bot = 20(5)45 {

local top = `bot' + 4

gen age`bot'to`top' = age >= `bot' & age <= `top'

}This will create dummy variables age20to24 to

age45to49. The way the loop works is that the local macro

bot will take values between 20 and 45 in steps of 5 (hence

20, 25, 30, 35, 40, and 45), the lower bounds of the age groups.

Inside the loop we create a local macro top to represent

the upper bounds of the age groups, which equals the lower bound plus 4.

The first time through the loop bot is 20, so

top is 24. We use an equal sign to store the result of

adding 4 to bot.

The next line is a simple generate statement. The first time through

the loop the line will say

gen age20to24 = age >= 20 & age <= 24, as you can

see by doing the macro substitution yourself. This will create the first

dummy, and Stata will then go back to the top to create the next

one.

5.2.2 Looping Over Elements in a List

The second looping command is foreach and comes in six

flavors, dealing with different types of lists. I will start with the

generic list:

foreach item in a-list-of-things {

... body of loop using `item' ...

}Here foreach is a keyword, item is a local

macro name of your own choosing, in is another keyword, and

what comes after is a list of blank-separated words. Try this

example

foreach animal in cats and dogs {

display "`animal'"

}This loop will print “cats”, “and”, and “dogs”, as the local macro

animal is set to each of the words in the list. Stata

doesn’t know “and” is not an animal, but even if it did, it wouldn’t

care because the list is generic.

If you wanted to loop over an irregular sequence of numbers –for example you needed to do something with the Coale-Demeny regional model life tables for levels 2, 6 and 12– you could write

foreach level in 2 6 12 {

... do something with `level' ...

}That’s it. This is probably all you need to know about looping.

5.2.3 Looping Over Specialized Lists

Stata has five other variants of foreach which loop over

specific types of lists, which I now describe briefly.

Lists of Variables

Perhaps the most useful variant is

foreach varname of varlist list-of-variables {

... body of loop using `varname' ...

}Here foreach, of and varlist

are keywords, and must be typed exactly as they are. The

list-of-variables is just that, a list of existing

variable names typed using standard Stata conventions, so you can

abbreviate names (at your own peril), use var* to refer to

all variables that start with “var”, or type var1-var3 to

refer to variables var1 to var3.

The advantages of this loop over the generic equivalent

foreach varname in list-of-variables is that Stata checks

that each name in the list is indeed an existing variable name, and lets

you abbreviate or expand the names.

If you need to loop over new as opposed to existing

variables use

foreach varname of newlist list-of-new-variables. The

newlist keyword replaces varlist and tells

Stata to check that all the list elements are legal names of variables

that don’t exist already.

Words in Macros

Two other variants loop over the words in a local or global macro;

they use the keyword global or local followed

by a macro name (in lieu of a list). For example here’s a way to list

the control variables from the section on local macros:

foreach control of local controls {

display "`control'"

}Presumably you would do something more interesting than just list the

variable names. Because we are looping over variables in the dataset we

could have achieved the same purpose using foreach with a

varlist; here we save the checking.

Lists of Numbers

Stata also has a foreach variant that specializes in

lists of numbers (or numlists in Stataspeak) that can’t be

handled with forvalues.

Suppose a survey had a baseline in 1980 and follow ups in 1985 and 1995. (They actually planned a survey in 1990 but it was not funded.) To loop over these you could use

foreach year of numlist 1980 1985 1995 {

display "`year'"

}Of course you would do something more interesting than just print the

years. A numlist may be specified as 1 2 3, or

1/5 (meaning 1 2 3 4 5), or 1(2)7 (count from

1 to 7 in steps of 2 to get 1 3 5 7); type help numlist for

more examples.

The advantage of this command over the generic foreach

is that Stata will check that each of the elements of the list of

numbers is indeed a number.

5.2.4 Looping for a While

In common with many programming languages, Stata also has a

while loop, which has the following structure

while condition {

... do something ...

}where condition is an expression. The loop executes as long as the condition is true (nonzero). Usually something happens inside the loop to make the condition false, otherwise the code would run forever.

A typical use of while is in iterative estimation

procedures, where you may loop while the difference in successive

estimates exceeds a predefined tolerance. Usually an iteration count is

used to detect lack of convergence.

The continue [,break] command allows breaking out of any

loop, including while, forvalues and

foreach. The command stops the current iteration and

continues with the next, unless break is specified, in

which case it exits the loop.

5.2.5 Conditional Execution

Stata also has an if programming command, not to be

confused with the ifqualifier that can be used to

restrict any command to a subset of the data, as in

summarize mpg if foreign. The

ifcommand has the following structure

if expression {

... commands to be executed if expression is true ...

}

else {

... optional block to be executed if expression is false ...

}Here if and the optional else are keywords,

and expression is a logical condition (type

help exp for an explanation of expressions). The opening

brace { must be the last thing on a line (other than

comments) and the closing brace } must be on a new line by

itself.

If the if or else parts consist of a single

command they can go on the same line without braces, as in

if expression command. But

if expression { command } is not legal. You could use the

braces by spreading the code into three lines, and this often improves

readability of the code.

So here we have a silly loop where we break out after five of the possible ten iterations:

forvalues iter=1/10 {

display "`iter'"

if `iter' >= 5 continue, break

}And with that, we break out of looping.

5.3 Writing Commands

We now turn to the fun task of writing your own Stata commands.

Follow along as we develop a few simple programs, ending with an

egen extension to evaluate the Coale-McNeil model

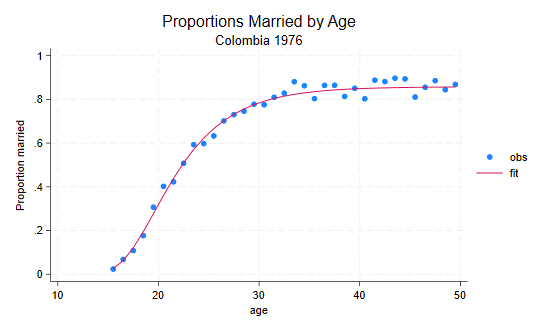

nuptiality schedule, so we can create a plot like the figure below.

5.3.1 Programs With No Arguments

There is a long tradition that the first program one writes in a new language is “Hello World!”. The simplest way to develop a new program is to start with a do file:

capture program drop hello

program define hello

version 14

display as text "hello, world"

endThat’s it. If you now type hello Stata will say “hello,

world”, in lowercase, with a comma, and without an exclamation mark,

just as Brian Kernighan’s original.

The program drop statement is needed in case we make

changes and need to rerun the do file, because you can’t define an

existing program. The capture is needed the very first

time, when there is nothing to drop.

The version is set to 14 so that users of earlier

versions of Stata can run the program. (I will do that for all programs

in this section, as they do not rely on more recent features.)

All Stata output goes through SMCL, pronounced “smickle” and short for Stata Markup Control Language. SMCL uses plain text combined with commands enclosed in braces. Below we use a bit of SMCL to frame this inmortal sentence

. capture program drop hello

. program define hello

1. version 14

2. display "{txt}{c TLC}{hline 14}{c TRC}"

3. display "{c |} hello, world {c |}"

4. display "{c BLC}{hline 14}{c BRC}"

5. end

. hello

┌──────────────┐

│ hello, world │

└──────────────┘

Here {txt} sets the style to text (as opposed to input,

error or result), {c TLC} and its cousins are used to draw

top-left, top-right, bottom-left and bottom-right corners,

{hline 14} draws a horizontal line 14 characters long, and

{c |} draws a tall |. To learn more about SMCL

type help smcl. This will be essential to write a help file

for your commands.

5.3.2 A Program with an Argument

To make useful programs you will often need to pass information to

them, in the form of “arguments” you type after the command. Let’s write

a command that echoes what you say. I used to call it echo,

but now Stata has its own (undocumented) echo program, so we’ll call it

parrot. (Stata reserves all english words, so you have to

be careful naming your programs. You can check if the name is taken by

typing which followed by the name, in our case

which parrot.)

capture program drop parrot

program define parrot

version 14

display "`0'"

endTry typing parrot hello, world to see what happens.

When you call a command Stata stores the arguments in a local macro

called 0. We use a display command with `0' to

evaluate the macro. The result is text, so we enclose it in quotes.

(Suppose you typed parrot hi, so the local macro

0 has hi; the command would read

display hi and Stata will complain, saying ‘hi not found’.

We want the command to read display "hi", which is why we

code display "`0'".)

If we don’t specify anything, the local macro 0 will be

an empty string, the command will read display "" and Stata

will print a blank line.

5.3.3 Compound Quotes

Before we go out to celebrate we need to fix a small problem with our

new command. Try typing parrot The hopefully "final" run.

Stata will complain. Why? Because after macro substitution the

all-important display command will read

display "The hopefully "final" run"The problem is that the quote before final closes the initial quote,

so Stata sees this is as "The hopefully " followed by

final" run", which looks to Stata like an invalid name.

Obviously we need some way to distinguish the inner and outer

quotes.

Incidentally you could see exactly where things went south by typing

set trace on and running the command. You can see in (often

painful) detail all the steps Stata goes through, including all macro

substitutions. Don’t forget to type set trace off when you

are done. Type help trace to learn more.

The solution to our problem? Stata’s compound double quotes:

`" to open and "' to close, as in

`"compound quotes"'. Because the opening and closing

symbols are different, these quotes can be nested. Compound quotes

- can be used anywhere a double quote is used.

- must be used if the text being quoted includes double quotes.

So our program must display `"`0'"'. Here’s the final

version.

program define parrot

version 14

if `"`0'"' != "" display as text `"`0'"'

endYou will notice that I got rid of the capture drop line.

I also used display as text to make sure we print using the

text style. For error messages you may want to use

display as error instead. Type help display to

learn more about this command.

We are now ready to save the program as an ado file.

Type sysdir to find out where your personal ado directory

is, and then save the file there with the name parrot.ado.

The command will now be available any time you use Stata.

5.3.4 Positional Arguments

In addition to storing all arguments together in local macro

0, Stata parses the arguments (using white space as a

delimiter) and stores all the words it finds in local macros

1, 2, 3, etc.

Typically you would do something with `1' and then move

on to the next one. The command mac shift comes handy then,

because it shifts all the macros down by one, so the contents of

2 is now in 1, and 3 is in

2, and so on. This way you always work with what’s in

1 and shift down. When the list is exhausted 1

is empty and you are done.

So here is the canonical program that lists its arguments

capture program drop listargs

program define listargs

version 14

while "`1'" != "" {

display `"`1'"'

mac shift

}

endDon’t forget the mac shift, otherwise your program may

run forever. (Or until you hit the break key.)

Try listargs one two three testing. Now try

listargs one "two and three" four. Notice how one can group

words into a single argument by using quotes.

This method is useful, and sometimes one can given the arguments more

meaningful names using args. We will give an example in

5.3.8. But let us discuss Stata syntax first, a more powerful and robust

approach.

(By the way one can pass arguments not just to commands, but to

do files as well. Type help do to learn more.)

5.3.5 Using Stata Syntax

If your command uses standard Stata syntax –which means the arguments

are a list of variables, possibly a weight, maybe an if or

in clause, and perhaps a bunch of options– you can

take advantage of Stata’s own parser, which conveniently stores all

these elements in local macros ready for you to use.

A Command Prototype

Let us write a command that computes the probability of marrying by a certain age in a Coale-McNeil model with a given mean, standard deviation, and proportion marrying. The syntax of our proposed command is

pnupt age, generate(married) [ mean(25) stdev(5) pem(1) ]So we require an existing variable with age in exact years, and a mandatory option specifying a new variable to be generated with the proportions married. There are also options to specify the mean, the standard deviation, and the proportion ever married in the schedule, all with defaults. Here’s a first cut at the command

capture program drop pnupt

program define pnupt

version 14

syntax varname, Generate(name) ///

[ Mean(real 25) Stdev(real 5) Pem(real 1) ]

// ... we don't do anything yet ...

endThe first thing to note is that the syntax command looks

remarkably like our prototype. That’s how easy this is.

Variable Lists

The first element in our syntax is an example of a list of

variables or varlist. You can specify minima and

maxima, for example a program requiring exactly two variables would say

varlist(min=2 max=2). When you have only one variable, as

we do, you can type varname, which is short for

varlist(min=1 max=1).

Stata will then make sure that your program is called with exactly

one name of an existing variable, which will be stored in a local macro

called varlist. (The macro is always called

varlist, even if you have only one variable and used

varname in your syntax statement.) Try

pnupt nonesuch and Stata will complain, saying “variable

nonesuch not found”.

(If you have done programming before, and you spent 75% of your time

writing checks for input errors and only 25% focusing on the task at

hand, you will really appreciate the syntax command. It

does a lot of error checking for you.)

Options and Defaults

Optional syntax elements are enclosed in square brackets

[ and ]. In our command the

generate option is required, but the other three are

optional. Try these commands to generate a little test dataset with an

age variable ranging from 15 to 50

drop _all

set obs 36

gen age = 14 + _nNow try pnupt age. This time Stata is happy with

age but notes ‘option generate() required’. Did I say

syntax saves a lot of work? Options that take arguments

need to specify the type of argument (integer,

real, string, name) and,

optionally, a default value. Our generate takes a

name, and is required, so there is no default. Try

pnupt age, gen(2). Stata will complain that 2 is not a

name.

If all is well, the contents of the option is stored in a local macro

with the same name as the option, here generate.

Checking Arguments

Now we need to do just a bit of work to check that the name is a

valid variable name, which we do with confirm:

confirm new variable `generate'Stata then checks that you could in fact generate this variable, and

if not issues error 110. Try pnupt age, gen(age) and Stata

will say ‘age already defined’.

It should be clear by now that Stata will check that if you specify a

mean, standard deviation or proportion ever married, abbreviated as

m(), s() and p(), they will be

real numbers, which will be stored in local macros called

mean, stdev, and pem. If an

option is omitted the local macro will contain the default.

You could do more checks on the input. Let’s do a quick check that all three parameters are non-negative and the proportion is no more than one.

if (`mean' <= 0 | `stdev' <= 0 | `pem' <= 0 | `pem' > 1) {

di as error "invalid parameters"

exit 110

}You could be nicer to your users and have separate checks for each parameter, but this will do for now.

Temporary Variables

We are now ready to do some calculations. We take advantage of the relation between the Coale-McNeil model and the gamma distribution, as explained in Rodríguez and Trussell (1980). Here’s a working version of the program

program define pnupt

*! Coale-McNeil cumulative nuptiality schedule v1 GR 24-Feb-06

version 14

syntax varname, Generate(name) [Mean(real 25) Stdev(real 5) Pem(real 1)]

confirm new var `generate'

if `mean' <= 0 | `stdev' <= 0 | `pem' <= 0 | `pem' > 1 {

display as error "invalid parameters"

exit 198

}

tempname z g

gen `z' = (`varlist' - `mean')/`stdev'

gen `g' = gammap(0.604, exp(-1.896 * (`z' + 0.805)))

gen `generate' = `pem' * (1 - `g')

end We could have written the formula for the probability in one line,

but only by sacrificing readability. Instead we first standardize age,

by subtracting the mean and dividing by the standard deviation. What can

we call this variable? You might be tempted to call it z,

but what if the user of your program has a variable called

z? Later we evaluate the gamma function. What can we call

the result?

The solution is the tempname command, which asks Stata

to make up unique temporary variable names, in this case two to be

stored in local macros z and g. Because these

macros are local, there is no risk of name conflicts. Another feature of

temporary variables is that they disappear automatically when your

program ends, so Stata does the housekeeping for you.

The line gen `z' = (`varlist' - `mean')/`stdev' probably

looks a bit strange at first. Remember that all names and values of

interest are now stored in local macros and we need to evaluate them to

get anywhere, hence the profusion of backticks: `z' gets

the name of our temporary variable, `varlist' gets the name

of the age variable specified by the user, `mean' gets the

value of the mean, and `stdev' gets the value of the

standard deviation. After macro substitution this line will read

something like gen _000001 = (age-22.44)/5.28, which

probably makes a lot more sense.

If/In

You might consider allowing the user to specify if and

in conditions for your command. These would need to be

added to the syntax, where they would be stored in local macros, which

can then be used in the calculations, in this case passed along to

generate.

For a more detailed discussion of this subject type

help syntax and select if and then

in. The entry in help mark is also

relevant.

5.3.6 Creating New Variables

Sometimes all your command will do is create a new variable. This, in

fact, is what our little command does. Wouldn’t it be nice if we could

use an egen type of command like this:

egen married = pnupt(age), mean(22.48) stdev(5.29) pem(0.858)Well, we can! As it happens, egen is user-extendable. To

implement a function called pnupt you have to create a

program (ado file) called _gpnupt, in other words add the

prefix _g. The documentation on egen extensions is a bit

sparse, but once you know this basic fact all you need to do is look at

the source of an egen command and copy it. (I looked at

_gmean.)

So here’s the egen version of our Coale-McNeil

command.

program define _gpnupt

*! Coale-McNeil cumulative nuptiality schedule v1 GR 24-Feb-06

version 14

syntax newvarname=/exp [, Mean(real 25) Stdev(real 5) Pem(real 1)]

if `mean' <= 0 | `stdev' <= 0 | `pem' <= 0 | `pem' > 1 {

display as error "invalid parameters"

exit 198

}

tempname z g

gen `z' = (`exp' - `mean')/`stdev'

gen `g' = gammap(0.604, exp(-1.896 * (`z' + 0.805)))

gen `typlist' `varlist' = `pem' * (1 - `g')

end There are very few differences between this program and the previous

one. Instead of an input variable egen accepts an

expression, which gets evaluated and stored in a temporary variable

called exp. The output variable is specified as a

varlist, in this case a newvarname. That’s why

z now works with exp, and gen

creates varlist. The mysterious typlist is

there because egen lets you specify the type of the output

variable (float by default) and that gets passed to our

function, which passes it along to gen.

5.3.7 A Coale-McNeil Fit

We are ready to reveal how the initial plot was produced. The data are available in a Stata file in the datasets section of my website, which has counts of ever married and single women by age. We compute the observed proportion married, compute fitted values based on the estimates in Rodríguez and Trussell (1980), and plot the results. It’s all done in a handful of lines

. use https://grodri.github.io/datasets/cohhnupt, clear (WFS Colombia Household Survey) . gen agem = age + 0.5 . gen obs = ever/total . egen fit = pnupt(agem), mean(22.44) stdev(5.28) pem(.858) . twoway (scatter obs agem) (line fit agem), /// > title(Proportions Married by Age) subtitle(Colombia 1976) /// > ytitle(Proportion married) xtitle(age) . graph export cohhnup.png, width(550) replace file cohhnup.png saved as PNG format

The actual estimation can be implemented using Stata’s maximum likelihood procedures, but that’s a story for another day.

5.3.8 Returning Results

So far our commands have printed results or created a new variable.

How do you return results to the user? A general command can declare

itself to be rclass and then return results in

r(), while an estimation command can declare

eclass and return results in e(). Let us

illustrate the former with a command to compute Tukey’s trimean T =

(Q1 + 2 Q2 + Q3)/4, a weighted average

of the quartiles and median.

. capture program drop trimean

. program trimean, rclass

1. version 14

2. args varname

3. confirm variable `varname'

4. quietly summarize `varname', detail

5. if r(N) == 0 {

6. display as error "No observations"

7. exit

8. }

9. tempname trimean

10. scalar `trimean' = (r(p25) + 2*r(p50) + r(p75))/4

11. display "trimean = ", `trimean'

12. return scalar trimean = `trimean'

13. end

The first thing to notice is that the program statement

includes the rclass option. This is required to be able to

return results.

We then use args to name the single argument

varname, and we then use confirm variable to

check that the variable exists. The quartiles we need are computed by

summarize with the detail option, which we do

quietly to skip printing the results. If the variable is a

string or all values are missing, summarize will set

r(N) to 0, in which case we display an error message and

exit.

We could store the trimean in a local macro, but we will lose

precision. Instead we use a scalar. The tempname line will

store a unique name in the local macro trimean. We then

store the trimean in a scalar with that name, and print it. The final

step uses the return statement to store the scalar result

in r(trimean). Let us run the program and then list the

results

. sysuse auto, clear

(1978 automobile data)

. trimean mpg

trimean = 20.75

. return list

scalars:

r(trimean) = 20.75

Each rclass command erases the results of the previous

one. However we could use return add to add our results to

what’s on r() already. Try it. After running our command,

return list will list 20 results, ready for inclusion in a

customized table.

We could expand the program to more variables, perhaps using

syntax varlist, but note that summarize only

stores results for the last variable listed, and our command should

probably do the same.

5.4 Other Topics

To keep this tutorial from becoming too long I have skipped or cut

short many topics. To learn more about returning results from your

commands type help return. For estimation commands, which

can post estimation results to e(), see

help ereturn and help _estimates. An essential

reference on estimation is Maximum Likelihood Estimation with

Stata, Fourth Edition, by Gould, Pitblado and Poi (2010).

Other subjects of interest are matrices (start with

help matrix), and how to make commands “byable” (type

help byable). To format your output you need to learn more

about SMCL, start with help smcl. For work on graphics you

may want to study class programming (help class) and learn

about sersets (help serset). To provide a graphical user

interface to your command try help dialog programming. It

is also possible to read and write text and binary files (see

help file).

The biggest omission here is Mata, a full-fledged matrix programming language that was introduced in Version 9 of Stata. Mata is compiled to byte code, so it is much faster than Stata’s classic ado programs. I find that the best way to write new Stata commands is to use classic ado for the user interface and Mata for the actual calculations. If you are interested in learning Mata I strongly recommend Gould’s (2018) The Mata Book.

Continue with References