3 Reading and Examining Data

R can handle several types of data, including numbers, character strings, vectors and matrices, as well as more complex data structures. In this section I describe data frames, the preferred way to organize data for statistical analysis, explain how to read data from an external file into a data frame, and show how to examine the data using simple descriptive statistics and informative plots.

3.1 Lists and Data Frames

An important data structure that we have not discussed so far is the list. A list is a set of objects that are usually named and can be anything: numbers, character strings, matrices or even lists.

Unlike a vector, whose elements must all be of the same type (all

numeric, or all character), the elements of a list may have different

types. Here’s a list with two components created using the function

list():

> person <- list(name="Jane", age=24)Typing the name of the list prints all elements.

> person$name

[1] "Jane"

$age

[1] 24You can extract a component of a list using the extract operator

$. For example we can list just the name or

age of this person:

> person$name[1] "Jane"> person$age[1] 24Individual elements of a list can also be accessed using their

indices or their names as subscripts. For example we can get the name

using person[1] or person["name"]. You can use

single or double square brackets. If you use single brackets, as we did

here, you get a list with the name. If you use double brackets you get

just the name. Try person[[1]] or

person[["name"]] to see the difference.

A data frame is essentially a rectangular array containing the values of one or more variables for a set of units. The frame also contains the names of the variables, the names of the observations, and information about the nature of the variables, including whether they are numerical or categorical.

Internally, a data frame is a special kind of list, where each element is a vector of observations on a variable. Data frames look like matrices, but can have columns of different types. This makes them ideally suited for representing datasets, where some variables can be numeric and others can be categorical.

Data frames (like matrices) can also accommodate missing values,

which are coded using the special symbol NA. Most

statistical procedures, however, omit all missing values.

Data frames can be created from vectors, matrices or lists using the

function data.frame(), but more often than not one will

read data from an external file, as shown in the next two sections.

3.2 Free-Format Input

Free-format data are text files containing numbers or character strings separated by spaces. Optionally the file may have a header containing variable names. Here’s an excerpt of a data file containing information on three variables for 20 countries in Latin America:

setting effort change

Bolivia 46 0 1

Brazil 74 0 10

Chile 89 16 29

... lines omitted ...

Venezuela 91 7 11This small dataset includes an index of social setting, an index of

family planning effort, and the percent decline in the crude birth rate

between 1965 and 1975. The data are available on my website in a file

called effort.dat that includes a header with the variable

names.

R can read the data directly from the web:

> fpe <- read.table("https://grodri.github.io/datasets/effort.dat")The function used to read data frames is read.table().

The argument is a character string giving the name of the file

containing the data, but here we have given it a fully qualified url

(uniform resource locator), and that’s all it takes.

Alternatively, you could download the data and save them in a local

file, or just cut and paste the data from the browser to an editor, and

then save them. Make sure the file ends up in R’s working directory,

which you can find out by typing getwd(). If that is not

the case, you can use a fully qualified path name or change R’s working

directory by calling setwd() with a string argument.

Remember to double up your backward slashes (or use forward slashes

instead) when specifying paths in Windows.

Here we assigned the data to an object called fpe. To

print the object you simply type its name

> fpe setting effort change

Bolivia 46 0 1

Brazil 74 0 10

Chile 89 16 29

Colombia 77 16 25

CostaRica 84 21 29

Cuba 89 15 40

DominicanRep 68 14 21

Ecuador 70 6 0

ElSalvador 60 13 13

Guatemala 55 9 4

Haiti 35 3 0

Honduras 51 7 7

Jamaica 87 23 21

Mexico 83 4 9

Nicaragua 68 0 7

Panama 84 19 22

Paraguay 74 3 6

Peru 73 0 2

TrinidadTobago 84 15 29

Venezuela 91 7 11In this example R detected correctly that the first line in our file

was a header with the variable names. It also inferred correctly that

the first column had the observation names. (Well, it did so with a

little help; I made sure the row names did not have embedded spaces,

hence CostaRica. Alternatively, I could have used

"Costa Rica" in quotes as a row name.)

You can always tell R explicitly whether or not you have a header by

specifying the optional argument header=TRUE or

header=FALSE to the read.table() function.

This is important if you have a header but lack row names, because R’s

guess is based on the fact that the header line has one fewer entry than

the next row, as it did in our example.

If your file does not have a header line, R will use the default

variable names V1, V2, …, etc. To override

this default use read.table()’s optional argument

col.names to assign variable names. This argument takes a

vector of names. So, if our file did not have a header we could

have used the command

> fpe <- read.table("noheader.dat", col.names=c("setting","effort","change"))Don’t worry if this command doesn’t fit in a line. R code can be

continued automatically in a new line simply by making it obvious that

we are not done, for example ending the line with a comma, or having an

unclosed left parenthesis. R responds by prompting for more with the

continuation symbol + instead of the usual prompt

>.

If your file does not have observation names, R will simply number

the observations from 1 to n. You can specify row names using

read.table()’s optional argument row.names,

which works just like col.names; type

?data.frame for more information. (I should mention that in

a “tidy” world row names should just be another column, but classic R

treats them as observation indices.)

There are two closely related functions that can be used to get or

set variable and observation names at a later time. These are

called names(), for the variable or column names, and

row.names() for the observation or row names. Thus, if our

file did not have a header we could have read the data and then changed

the default variable names using the names() function:

> fpe <- read.table("noheader.dat")

> names(fpe) <- c("setting","effort","change")Technical Note: If you have a background in other programming languages, you may be surprised to see a function call on the left hand side of an assignment. These are special replacement functions in R. They extract an element of an object and then replace its value.

In our example all three-variables were numeric. R will handle categorical variables with no problem, including factors and string variables. In Section 4 we will create a factor, basically a categorical variable that takes one of a finite set of values called levels, by grouping a numeric covariate into categories. In Section 5 we will read a dataset that includes string variables with values such as “low” and “high”. These can be converted to factors or kept as character data.

Exercise: Use a text editor to create a small file with the following three lines:

a b c

1 2 3

4 5 6Read this file into R so the variable names are a,

b and c. Now delete the first row in the file,

save it, and read it again into R so the variable names are still

a, b and c.

3.3 Fixed-Format Input

Suppose the family planning effort data had been stored in a file containing only the actual data (no country names or variable names) in a fixed format, with social setting in character positions (often called columns) 1-2, family planning effort in positions 3-4 and fertility change in positions 5-6. This is a fairly common way to organize large datasets.

The following call will read the data into a data frame and name the variables:

> fpe <- read.table("fixedformat.dat", col.names = c("setting", "effort",

"change"), sep=c(1, 3, 5))Here I assume that the file in question is called

fixedformat.dat. I assign column names just as before,

using the col.names parameter. The novelty lies in the next

argument, called sep, which is used to indicate how the

variables are separated. The default is white space, which is

appropriate when the variables are separated by one or more blanks or

tabs. If the data are separated by commas, a common format with

spreadsheets, you can specify sep = ",". Here I created a

vector with the numbers 1, 3 and 5 to specify the character position (or

column) where each variable starts. Type ?read.table for

more details.

3.4 Printing Data and Summaries

You can refer to any variable in the fpe data frame

using the extract operator $. For example to look at the

values of the fertility change variable, type

> fpe$change [1] 1 10 29 25 29 40 21 0 13 4 0 7 21 9 7 22 6 2 29 11and R will list a vector with the values of change for the 20

countries. You can also define fpe as your default dataset

by “attaching” it to your session:

> attach(fpe)If you now type the name effort by itself, R will now

look for it in the fpe data frame. If you are done with a

data frame, you can detach it using detach(fpe). While

attach() can save typing, experience has shown that it can

also lead to problems, suggesting it is best avoided. For example, if

you already have an object named effort, that will mask the

object in fpe. My advice is to always specify the data

frame name, as we do below.

To obtain simple descriptive statistics on these variables try the

summary() function:

> summary(fpe) setting effort change

Min. :35.0 Min. : 0.00 Min. : 0.00

1st Qu.:66.0 1st Qu.: 3.00 1st Qu.: 5.50

Median :74.0 Median : 8.00 Median :10.50

Mean :72.1 Mean : 9.55 Mean :14.30

3rd Qu.:84.0 3rd Qu.:15.25 3rd Qu.:22.75

Max. :91.0 Max. :23.00 Max. :40.00 As you can see, we get the min and max, 1st and 3rd quartiles, median

and mean. For categorical variables you get a table of counts.

Alternatively, you may ask for a summary of a specific variable. Or use

the functions mean() and var() for the mean

and variance of a variable, or cor() for the correlation

between two variables, as shown below:

> mean(fpe$effort)[1] 9.55> cor(fpe$effort, fpe$change)[1] 0.8008299Elements of data frames can be addressed using the subscript notation introduced in Section 2.3 for vectors and matrices. For example to list the countries that had a family planning effort score of zero we can use

> fpe[fpe$effort == 0, ] setting effort change

Bolivia 46 0 1

Brazil 74 0 10

Nicaragua 68 0 7

Peru 73 0 2This works because the expression fpe$effort == 0

selects the rows (countries) where the effort score is zero, while

leaving the column subscript blank selects all columns (variables).

The fact that the rows are named allows yet another way to select elements: by name. Here’s how to print the data for Chile:

> fpe["Chile", ] setting effort change

Chile 89 16 29Exercise: Can you list the countries where social setting is

high (say above 80) but effort is low (say below 10)? Hint: recall the

element-by-element logical operator &.

3.5 Plotting Data

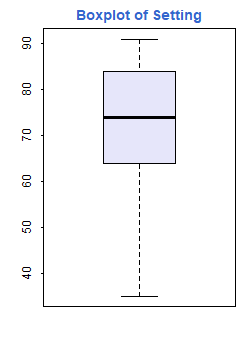

Probably the best way to examine the data is by using graphs. Here’s

a boxplot of setting. Inspired by a demo included in the R distribution,

I used custom colors for the box (“lavender”, specified using a name R

recognizes) and the title (#3366CC).

As noted earlier, R can save a plot as a png or jpeg file, so that it can be included directly on a web page. Other formats available are postscript for printing and windows metafile for embedding in other applications. Note also that you can cut and paste a graph to insert it in another document.

> boxplot(fpe$setting, col="lavender")

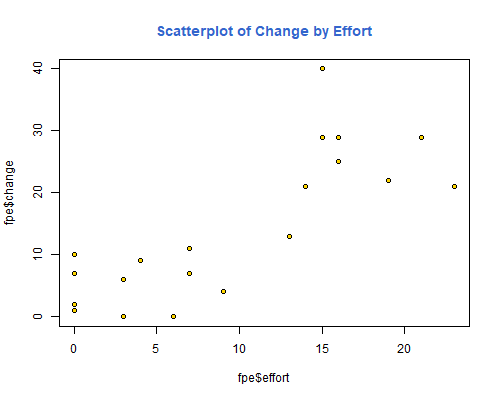

> title("Boxplot of Setting", col.main="#3366CC")Here’s a scatterplot of change by effort, so you can see what a correlation of 0.80 looks like:

> plot(fpe$effort, fpe$change, pch=21, bg="gold")

> title("Scatterplot of Change by Effort", col.main="#3366CC")

I used two optional arguments that work well together:

pch=21 selects a special plotting symbol, in this case a

circle, that can be colored and filled; and bf="gold"

selects the fill color for the symbol. I left the perimeter black, but

you can change this color with the col argument.

To identify points in a scatterplot use the identify()

function. Try the following on the graph window:

> identify(fpe$effort, fpe$change, row.names(fpe), ps = 9)The first three parameters to this function are the x and y

coordinates of the points and the character strings to be used in

labeling them. The ps optional argument specifies the size

of the text in points; here I picked 9-point labels.

Now click within a quarter of an inch of the points you want to

identify. R Studio will note that “locator is active”. When you are done

clicking press the Esc key. The labels will then appear

next to the points you clicked on. (If you are using the R GUI, the

labels will appear as you click on the points.)

Which country had the most effort but only moderate change? Which one had the most change?

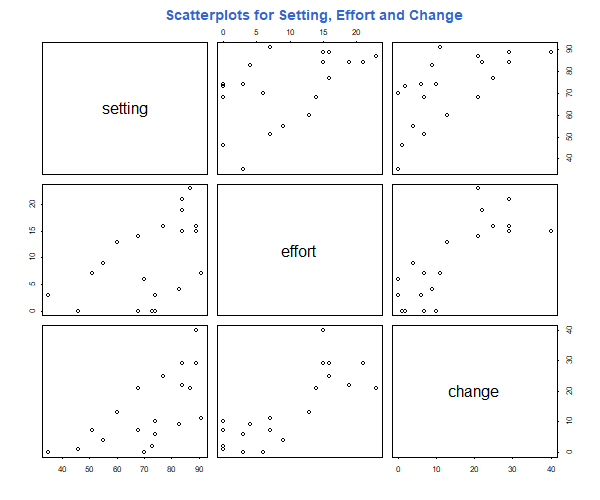

Another interesting plot to try is pairs(), which draws

a scatterplot matrix. In our example try

pairs(fpe)

title("Scatterplots for Setting, Effort and Change", col.main="#3366CC")

The result is a 3 by 3 matrix of scatterplots, with the variable names down the diagonal and plots of each variable against every other one.

Before you quit this session consider saving the fpe

data frame. To do this use the save() function

> save(fpe, file="fpe.Rdata")

> load("fpe.Rdata")The first argument specifies the object to be saved, and the

file argument provides the name of a file, which will be in

the working directory unless a full path is given. (Remember to

double-up your backslashes in Windows, or use forward slashes

instead.)

By default R saves objects using a compact binary format which is

portable across all R platforms. There is an optional argument

ascii that can be set to TRUE to save the

object as ASCII text. This option was handy to transfer R objects across

platforms, but is no longer needed.

You can also save an image of your entire workspace, including all objects you have defined, and then load everything again, using

> save.image(file = "workspace.Rdata")

> load("workspace.Rdata")In R Studio you can also do this using the Environment tab on the top

right; click on the floppy disk image to save the workspace, or on the

folder with an arrow to load a workspace. (In the R Gui you can use the

main menu; choose File|Save and

File|Load.)

When you quit R using q() you will be prompted to save

the workspace, unless you skip this safeguard by typing

q("no").

Exercise: Use R to create a scatterplot of change by setting, cut and paste the graph into a document in your favorite word processor, and try resizing and printing it. I recommend that you use the windows metafile format for the cut and paste operation.

Continue with Linear Models