3.4 The Comparison of Several Groups

We now consider the comparison of more than two groups. We will illustrate using the data on contraceptive use by age, where we compare four groups.

A k-by-two Table

These are the data on page 18 of the notes, entered as four age groups

. clear

. input ageg users nonusers

ageg users nonusers

1. 1 72 325

2. 2 105 299

3. 3 237 375

4. 4 93 101

5. end

. label define ageg 1 "<25" 2 "25-29" 3 "30-39" 4 "40-49"

. label values ageg ageg

. gen n = users + nonusers

. list

┌────────────────────────────────┐

│ ageg users nonusers n │

├────────────────────────────────┤

1. │ <25 72 325 397 │

2. │ 25-29 105 299 404 │

3. │ 30-39 237 375 612 │

4. │ 40-49 93 101 194 │

└────────────────────────────────┘

The One-Factor Model

Here is the model treating age as a factor with four levels, which is

of course saturated for the data. We will store the estimates for later

use. Stata can save estimates on disk using estimates save

or keep them in memory with estimates store. We’ll use the

latter.

. glm users i.ageg, family(binomial n)

Iteration 0: log likelihood = -12.323383

Iteration 1: log likelihood = -12.323383

Generalized linear models Number of obs = 4

Optimization : ML Residual df = 0

Scale parameter = 1

Deviance = 6.66091e-16 (1/df) Deviance = .

Pearson = 4.31348e-20 (1/df) Pearson = .

Variance function: V(u) = u*(1-u/n) [Binomial]

Link function : g(u) = ln(u/(n-u)) [Logit]

AIC = 8.161692

Log likelihood = -12.32338328 BIC = 6.66e-16

─────────────┬────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

│ OIM

users │ Coefficient std. err. z P>|z| [95% conf. interval]

─────────────┼────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

ageg │

25-29 │ .4606758 .1727255 2.67 0.008 .1221401 .7992116

30-39 │ 1.048293 .1544406 6.79 0.000 .7455952 1.350991

40-49 │ 1.424638 .1939574 7.35 0.000 1.044488 1.804788

│

_cons │ -1.507159 .1302529 -11.57 0.000 -1.76245 -1.251868

─────────────┴────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

. estimates store mageg

Compare the parameter estimates with those on Table 3.5 of the notes.

Can you obtain these estimates by hand directly from the raw

frequencies? We see that the odds of using contraception increase

steadily from one age group to the next. You could type

glm, eform to convert from logit coefficients to odds

ratios.

To test the significance of the age effects we can use a likelihood

ratio test comparing this model with the null, or a Wald test. Let us

start with the former. In Stata we need to fit the null model, which we

do quietly, before using lrtest

. quietly glm users, family(binomial n) . estimates store null . estimates restore mageg // for later use (results mageg are active now) . lrtest null mageg Likelihood-ratio test Assumption: null nested within mageg LR chi2(3) = 79.19 Prob > chi2 = 0.0000

The value of 79.19 on 3 d.f. means that we can reject the hypothesis that the probability of using contraception is the same in the four age groups.

Now for the Wald test, which is easily obtained using the

testparm command. Here’s the test for the age effect on

page 20 of the notes:

. testparm i.ageg

( 1) [users]2.ageg = 0

( 2) [users]3.ageg = 0

( 3) [users]4.ageg = 0

chi2( 3) = 74.36

Prob > chi2 = 0.0000

Once again the likelihood ratio and Wald test are similar, but not identical.

Finally, we will compute the fitted logits, which we will need later.

We can do this using the predict command, with the

xb option to make predictions in the scale of the linear

predictor, which in this case is the logit scale. (The default is to

predict in the scale of the response, in this case counts.)

. predict obslogit, xb

A One-variate Model

We will now treat age as a covariate, using the mid-points of the

four age groups; so we treat the group 15-24 as 20, 25-29 as 27.5, 30-39

as 35 and 40-49 as 45. (If these don’t look like mid-points to you, note

that age is usually reported in completed years, so 15-24 means between

15.0 and 25.0, and the mid-point is 20.0.) The easiest way to code the

midpoints in this example is via the recode command.

. recode ageg 1=20 2=27.5 3=35 4=45, gen(agem) (4 differences between ageg and agem)

We can now fit the model on page 20 of the notes, which has a linear effect of age:

. glm users agem, family(binomial n)

Iteration 0: log likelihood = -13.525129

Iteration 1: log likelihood = -13.525059

Iteration 2: log likelihood = -13.525059

Generalized linear models Number of obs = 4

Optimization : ML Residual df = 2

Scale parameter = 1

Deviance = 2.403351895 (1/df) Deviance = 1.201676

Pearson = 2.410763716 (1/df) Pearson = 1.205382

Variance function: V(u) = u*(1-u/n) [Binomial]

Link function : g(u) = ln(u/(n-u)) [Logit]

AIC = 7.76253

Log likelihood = -13.52505922 BIC = -.3692368

─────────────┬────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

│ OIM

users │ Coefficient std. err. z P>|z| [95% conf. interval]

─────────────┼────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

agem │ .060671 .0071034 8.54 0.000 .0467486 .0745934

_cons │ -2.672667 .2332492 -11.46 0.000 -3.129827 -2.215507

─────────────┴────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

. di exp(_b[agem])

1.0625493

We see that older women are more likely to use contraception, and that the odds of using contraception are about six percent higher for every year of age. (This comes from exponentiating the coefficient of age, which is now measured in years.)

We can formaly test the assumption of linearity using a likelihood

ratio test to compare this model with the saturated model of the

previous section. The test can be calculated using Stata’s

lrtest command, which uses a dot to refer to the

current model.

. lrtest . mageg Likelihood-ratio test Assumption: . nested within mageg LR chi2(2) = 2.40 Prob > chi2 = 0.3007

The chi-squared statistic of 2.4 on one d.f. is not significant, indicating that we have no evidence against the assumption of linearity, and can happily save two degrees of freedom. This statistic is, of course, the deviance for the model with a linear effect of age.

We can also calculate the deviance “by hand” from first principles, using the “sum of observed times log(observed/expected)” formula . Just remember that you need to use observed and expected counts of both successes and failures, here users and non-users:

. predict pusers // predicted count of users (option mu assumed; predicted mean users) . gen di = 2*(users*log(users/pusers) + (n-users)*log((n-users)/(n-pusers))) . quietly summarize di . display "Deviance = ", r(sum) Deviance = 2.4033537

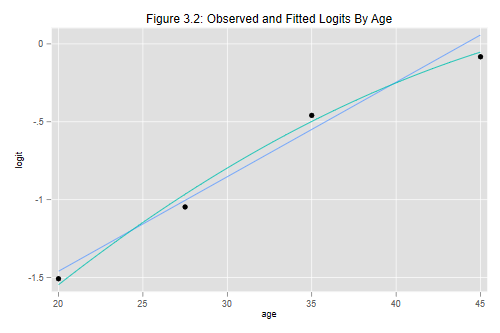

Observed and Fitted Logits

The next step will be to compute fitted logits based on this model, and use them together with the observed logits calculated earlier to examine visually the adequacy of the linear specification, effectively reproducing Figure 3.2 in the notes. For added measure I will also consider a model with a quadratic term, centering age around 30 before squaring it, so the linear term reflects the slope at 30.

. predict lfit1, xb

. gen agemcsq = (agem-30)^2

. quietly glm users agem agemcsq, family(binomial n)

. graph twoway (scatter obslogit agem) (line lfit1 agem) ///

> (function f=_b[_cons]+_b[agem]*x+_b[agemcsq]*(x-30)^2, ///

> range(20 45)) ///

> , title("Figure 3.2: Observed and Fitted Logits By Age") ///

> xtitle("age") ytitle("logit") legend(off)

. graph export fig32.png, width(500) replace

file fig32.png saved as PNG format

The graph shows that the linear specification was adequate. There is a hint that a quadratic model might be better, particularly in terms of the fit for the oldest age group, but the quadratic term is not significant.

You may wonder why I used functions to graph the fitted lines. Plotting the fitted values joined by line segments works fine for the linear model, but doesn’t reflect well the curvilinearity of the quadratic model, which is better represented using a function based on the coefficients.

This analysis gives us a quick indication of whether we could treat age linearly if we were working with individual data and had the actual ages of the 1607 women. It is not equivalent, however, because we have grouped age, and therefore treated all women men aged 25-29 as if they were age 27.5. With individual data some would be 25, some 26, etc.

You may also wonder why we were able to do a likelihood ratio test, when a model treating age linearly is usually not nested in a model that treats it as a factor. The answer is that in this case both specifications are applied to grouped data. You can view the linear model as imposing constraints, where the differences betwen the age groups are proportional to the difference in years between their midpoints. Alternatively, you can view the model that treats age as four groups as equivalent to having linear, quadratic, and cubic terms on the midpoints. Go ahead, try it. I’ll wait.

Updated fall 2022